(30

March 2023) How

inclusive is the

Nepali state?

Let's ask the 2021

census!

Since 1990,

the Nepali state has

committed itself in

its constitutions to

multiethnicity,

multilingualism and

religious diversity

in its society. This

reality was

reaffirmed in the

current constitution

of 2015. At the same

time, another

commitment was

added, namely that

of ending the

existing unequal

participation of

diverse social

groups in the state.

In 2006, during Jana

Andolan II, this had

been one of the most

urgent concerns of

the people and had

subsequently been

declared a priority

goal by all

political parties.

Yet this concern was

not entirely new in

2006. It had been

raised by members of

disadvantaged groups

as early as 1990,

but had not really

been heard. The

Nepal Janajati

Mahasangh, now Nepal

Adivasi Janajati

Mahasangh, the

alliance of

representative

organisations of

ethnic groups, was

still in its infancy

at the beginning of

the 1990s. Similar

representations of

the interests of the

Madheshi and Dalits

were more or less

nowhere in sight.

Historical

manipulations of the

census

In order to be able

to estimate the

extent of the

participation of the

various population

groups today, one

must first know how

high the population

share of the

respective groups is

in the total

society. Until now,

a look at the

published data of

the census, which

has been published

more or less

regularly every ten

years since 1911,

has provided

information on this.

For a long time, the

last well-founded

census with detailed

data on ethnic

groups/castes,

languages and

religions had been

the 1961 census,

which was compiled

immediately after

Mahendra's royal

coup in 1960 and was

still largely free

of the manipulations

of the panchayat

system. The

party-less royal

panchayat system

focused on faking a

cultural unitary

state in the decades

that followed. The

impact of this

policy can be seen

in the published

data of the 1971 and

1981 censuses. The

number of ethnic

groups listed

constantly

decreased, as did

the number of mother

tongues and their

speakers. At the

same time, the

pretended number of

practising Hindus

rose to almost 90

per cent.

The evidence for the

obviously fake data

was provided by the

censuses after the

democratisation of

1990, according to

which the proportion

of Hindus fell to

around 80 per cent

(2001). The

proportion of native

Nepali speakers fell

from 58.4 per cent

(1981) to 44.6 per

cent (2011). While

44 mother tongues

were counted in

1952/3, their number

dropped to 17

(1971). In the 2011

census, 123 mother

tongues were then

listed by name. All

this was to be seen

as a positive

development with

regard to the

appropriate

inclusion of all

social groups.

Shortcomings of the

2021 Census

And now the census

of 2021, whose data

was published barely

one and a half years

after it was

collected. However,

if you look for the

latest data on the

aforementioned

social and cultural

areas, you will be

surprised to find

that there are

absolutely no

figures. This did

not even happen

under the royal

panchayat system,

although this system

actually aimed at

avoiding such data.

At best, a

justification is

provided by point

13.5 of the

introductory notes

of the new census,

which states:

"People’s

aspirations and

expectations have

been elevated by the

new Constitution.

Issues of identities

and capturing

government’s

attention are high.

As a result, some

interest groups

tried to manipulate

the respondents’

independent answers

and dictated the

enumerators to write

a particular

response. But this

was independently

verified and a press

note was released

from the CBS no

fying all the

concerned parties

for possible legal

action if they did

not seize

campaigning with

prejudice. Moreover,

a number of interest

groups especially

related to

caste/ethnicity,

religion and

language have shown

serious concern on

census results and

presented their

specific demands

which need to be

dealt with higher

government or

political level."

This explanation is

very significant in

many respects. First

of all, the very

special importance

of identity is

emphasised. This can

only be emphatically

confirmed. It gives

people a very

individual personal

position in the

multi-ethnic,

multi-lingual and

multi-religious

state of Nepal.

Beyond that,

however, it also has

very special

political and

administrative

significance. Let's

just take the right

to vote, which in

the proportional

system refers to the

very figures

published in the

census for

percentage

allocation. The

figures must also be

made public in order

to comply with the

inclusion

regulations in the

political and

administrative

sphere.

Then the above quote

goes on to say that

some vested

interests have tried

to manipulate the

data collection in

this regard. Nepal's

constitution

guarantees the

fundamental right to

information. If the

CBS makes such

allegations in such

an important

document as the

census report, then

these vested

interests must be

named and legal

action must be taken

immediately. While

the CBS speaks of

having threatened

such legal action,

it remains unclear

whether it has been

initiated.

In this context,

there is talk of

"concerned parties".

Does this refer to

political parties or

to "groups" in

general? The next

sentence talks about

"interest groups

related to

caste/ethnicity,

religion and

language", which

obviously had

concerns about such

social data. Who are

these groups and

what are the reasons

for their concerns?

The bottom line is

that, while passage

13.5 of the

introductory remarks

to the census

explains problems

encountered during

the survey, it does

not explain why, for

the first time, the

census does not

include any data on

ethnicity, languages

and religions. In

view of the special

political, electoral

and administrative

significance of such

data, the Census

loses quite

considerably in

value, however good

and informative the

data now published

may be. Here, the

public interest of

the population and

the state is clearly

to be valued higher

than possible

reservations of

certain groups or

individuals.

So to return to the

initial question:

What has been

achieved so far of

the inclusion

promised by all

political parties in

2006? For this, the

public would not

only have to be

provided with new

basic social data on

ethnicity, languages

and religions, but

the respective

proportion would

also have to be

shown for all

possible areas of

public life. It

would be one of the

most important tasks

of the census in

general to provide

such data.

In order to

recognise that male

Khas Arya,

especially Bahun,

hold many times the

posts and functions

in the state system

that are appropriate

to them on the basis

of their population

share, new census

data is not

necessarily needed.

But it is also

important to

recognise changes in

the field of

inclusion. This is

also and especially

important for

classifying possible

positive changes

with regard to

traditionally

excluded population

groups.

So the vague hope

remains that the

missing data will

still be supplied.

There is no

indication of this.

Such data should

actually be taken

into account and

integrated in the

tables already

published. But this

is hardly likely to

happen. Only then

would it be possible

to see whether the

various social

groups in the areas

covered by the

census are affected

or involved

differently. The

question remains:

Are there specific

reasons why the

social data were

swept under the

table? Possibly,

they could prove the

failure of the

previous inclusion

policy and, on the

other hand, give

impetus to demands

of the excluded

groups to remedy

deficiencies.

(19

February 2023) Let's

celebrate National

Oligarchy Day!

In

Nepal, they celebrate

Democracy Day for three

days, whatever there is

to celebrate. 72 years

ago, the then King

Tribhuvan returned to

Nepal from exile in

India and promised the

people democracy, which

is still celebrated

today. In reality, of

course, it was all stink

and lies, as we all

know. In the years that

followed, the monarchy

did everything it could

to regain and secure its

absolutist power, which

ultimately ended in the

almost 30-year-long

party-less Panchayat

system.

The last king,

Gyanendra, who was

deposed in 2008, has

just once again proposed

a cooperation between

the monarchy and

political parties, for

the "preservation of

democracy", as he

explained. The question

remains why an

institution that has

been rightly abolished

is allowed to speak at

all; this only

exacerbates the crisis.

What is celebrated today

as democracy is in

reality an oligarchy of

a few ageing

politicians, all of whom

have failed repeatedly,

but who still consider

themselves

irreplaceable.

Twice since 1951 it

looked like democracy

would prevail: in 1990

after the first people's

movement (Jana Andolan

I) and in 2006 after

Jana Andolan II and the

ending of Gyanendra's

coup. The new

constitution of 2015 was

the work of the top

politicians of the major

parties and brought no

real democratic

advantage for the

people; it served

primarily to secure the

power of the

aforementioned party

elites.

In recent weeks, symbols

and ideals of Nepali

history that had long

been hoped to be

overcome have been

repeatedly celebrated.

On 11 January, for

example, the birthday of

Prithvi Narayan Shah,

the founder of modern

Nepal, was officially

celebrated for the first

time in years. This may

have been a gesture

towards the increasingly

vocal supporters of a

return to monarchy and

the Hindu state. After

all, the party that had

taken up this

unconstitutional cause

had to be integrated

into the allegedly

Maoist-communist

government for reasons

of securing power. The

Rastriya Prajatantra

Party (RPP) was founded

in 1990 as a rallying

point for the top

politicians of the

party-less royal

Panchyat system, has

split and merged again

and again, and is

bobbing along in

elections in low

single-digit

percentages. So much

only for the

significance of this

party.

Prithvi Narayan deserves

credit for unifying the

country to a certain

political greatness with

his brutal campaigns of

conquest. Otherwise,

Nepal would probably not

exist today. However, he

did not do this out of

great political

foresight, as is

repeatedly claimed, but

simply for reasons of

personal power and

economic advantage. But

this nation-wide seizure

of power by the Shah

dynasty of Gorkha also

had very serious

disadvantages for the

people in the conquered

areas, which are

generally kept quiet:

Destruction of

traditional local land

tenure rights, granting

of ethnic land to

supporters of the

monarchy, suppression of

ethnic and regional

cultures and languages,

integration of these

groups at a lower level

into the Hindu caste

system, to name but a

few. This laid the

foundations for the

unitary state later

sought by King Mahendra

and his son Birendra:

one language, one

religion, one culture,

one ethnicity, all

united by the glorious

bond of attachment of

the "subjects" to the

Shah monarchy.

The next big celebration

this year was the

anniversary of the

Maoist uprising on 13

February. Prime Minister

PK Dahal has now

declared it a National

Holiday for the first

time because of the

glorious achievements of

the uprising. The

uprising, which was

marked by heavy losses

and serious crimes and

human rights violations

by both Maoists and

state security forces,

has brought few

significant changes,

some of which are

increasingly being

challenged: Secularism,

federalism, republic.

The social inclusion

promised by all

political parties in

2006 is more distant

than ever. Thousands of

victims of the uprising

continue to wait in vain

for justice. Only a few

perpetrators from the

time of the uprising

have been convicted so

far. It is significant

that one of those

perpetrators has now

been pardoned as part of

the usual action on the

occasion of Democracy

Day.

And so now, three-day

celebrations of

democracy, that is, the

rule of the people.

These people have

recently expressed in

elections what they want

and what they do not

want. For example, they

have made it clear that

they no longer want this

old failed guard of male

Khas Arya politicians,

including those of the

previous ruling

alliance, who had tried

to maintain their power

through extreme

anti-democratic

manipulation of the

electoral system, or

those who in 2020/21 had

accepted the destruction

of Nepal's parliamentary

system in order to

maintain their personal

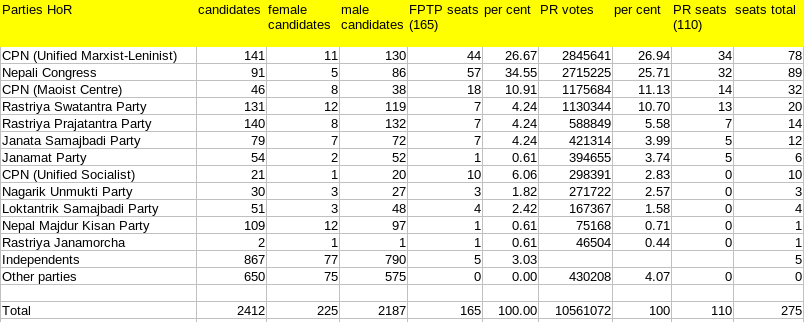

power. Only the PR

system allows a

statement on the status

of the political parties

and here the losses of

the three big parties

were clear: Nepali

Congress -7%, CPN (UML)

-6.3%, CPN (MC) -2.5%.

At the same time,

parties that offered

themselves as

alternatives experienced

a huge boost.

Unfortunately, after the

elections, some of these

alternative forces

turned out to be renewed

kingmakers to keep the

failed old politicians

in power, instead of

finally forcing them to

make a generational

change. Nepal has

already experienced

something similar after

the 2017 elections, when

the Bibeksheel Sajha

Party managed positive

approaches of an

alternative political

force before its leader

Rabindra Mishra then

outed himself as a

monarchist, who is now a

member of the RPP.

Positive approaches like

those of the Rastriya

Swatantra Party (RSP)

obviously lose their

impact as soon as the

traditional power

merry-go-round of the

ruling oligarchy takes

effect.

Thus, Nepal now has a

prime minister whose

party received just 11

per cent of the vote and

which won at least some

of the direct mandates

only thanks to the

manipulative electoral

alliance of the then

ruling parties. So Dahal

is prime minister thanks

to the direct votes of,

for example, traditional

NC voters, but this has

forced it into

opposition, which this

party, in turn, does not

see that way. Democracy

in Nepal supposedly does

not need an opposition.

At the same time, the

strings in the

background of the

current government are

pulled by KP Oli, who

two years ago led

Nepal's political system

to the brink of ruin. It

took his removal by the

Supreme Court to stop

him and his state

president who was loyal

to him.

And Oli would not be Oli

if he did not focus

everything on his quick

return to power. A year

and a half ago, Dahal

had played a decisive

role in Oli's downfall,

allegedly because he no

longer considered him

tenable. Now, however,

the post of prime

minister was more

important to Dahal than

his blather of

yesterday. But Dahal was

to pay dearly for his

post. Oli insisted on

about a third of the

ministerial posts for

his party. In addition,

he wanted all important

new state posts to be

reserved for the UML. At

some point, Dahal must

have realised that he

was only a puppet in

Oli's power game. Since

Dahal knows better than

anyone else how to fly

his flag with the wind

and to throw away

yesterday's promises,

the signs within the

governing coalition are

now pointing to a storm.

Oli and Dahal have

agreed that the post of

prime minister should

switch to Oli after two

and a half years,

however this is to be

handled legally, but

constitutional rules do

not interest Nepal's

failed top politician

anyway. Of utmost

importance for Oli is

that he then has a state

president at his side

who will rubber-stamp

his every potential

executive decision

unchecked, as Bidya Devi

Bhandari has willingly

done repeatedly. So Oli

still needs this post of

state president for his

party to have the state

machinery more or less

under his control.

Within no time, Oli

would then be back where

he was dishonourably

dismissed in 2021. Why

the latter did not have

further political

consequences for him

remains incomprehensible

anyway.

If the election of a new

state president were in

the interest of the

country and its people,

then this choice would

fall on a neutral

personality from the

realm of civil society.

But as it is, it is once

again an important

element in the power

game of the failed

political elites and

parties. Nepal remains

an oligarchy and not a

democracy. So let's

celebrate National

Oligarchy Day!

(25

December 2022)

The dishonesty of

Nepal's top

politicians

Free and fair elections

are the best non-violent

way for the citizens of

the country to express

their views to the

politicians and their

parties. Despite

tremendous manipulation

and restriction of the

freedom of choice

through the formation of

electoral alliances,

especially those of the

ruling parties, the

voters managed to

express a few things

clearly;

-

They did not want

"business as usual".

-

They did not want the

same old failed

politicians.

-

They wanted a

generational change in

political

responsibility.

And the signals were

clear. The electoral

alliance of the five

governing parties was

voted out because it

could no longer obtain

the number of MPs needed

to form a government.

The main opposition

party CPN (UML) led by

former two-time prime

minister KP Oli also

lost not only 36 direct

mandates compared to

2017, which was probably

due to the electoral

alliance of the ruling

parties, but also 6.3

per cent of the PR

votes, which was a

significant drop in

terms of voters' favour.

Similarly, the CPN

(MC)'s support dropped

again by 2.5 per cent to

only 11.1 per cent of

the PR vote, a trend

that has continued

unabated since 2008.

Presumably, this party

was only able to win

many of its 18 direct

mandates thanks to the

electoral alliance, in

which the other

participating parties

asked their voters to

vote for the candidate

of the Maoist party.

And what was the

reaction of the ageing

leaders of these three

parties to the clear

statement of the voters?

They saw themselves as

winners despite their

defeats, a phenomenon

that is not entirely

untypical after

elections worldwide. A

compromise solution

might have been to

transfer the

responsibility to a

younger generation. With

Gagan Thapa, a certainly

suitable candidate had

come forward.

But the old, failed top

politicians rigorously

ignored this option.

Instead, the parties in

the Deuba government,

for example, tried to

bring other parties on

board in order to come

up with the number of

MPs needed to continue

the government. At the

same time, a fierce

battle began between two

top leaders of the

ruling coalition, PK

Dahal and SB Deuba, for

the post of the future

prime minister.

Meanwhile, the

opposition leader KP Oli

pretended to accept

defeat and to remain in

opposition. In reality,

however, he did not miss

any opportunity to drive

discord into the

government coalition by

repeatedly calling for a

coalition of left

parties, preferably

under his leadership.

These power struggles

over the new government

formation had one thing

in common. They showed

that the top politicians

of the three big parties

were once again not

concerned with the

welfare of the state and

society, but solely with

fulfilling their own

personal claims to

power. In this respect,

PK Dahal's statement on

25 December that he now

had to change sides

because SB Deuba had

broken his promise when

he refused to accept

Dahal as the new prime

minister is striking.

Yet the voters had

expressed that they no

longer wanted either of

them.

It is shocking that

Dahal justifies his

switch to the Oli camp

by saying that he was

cheated by Deuba. But

how should the voters

who voted for the

candidates of the ruling

alliance feel, even if

these candidates came

from parties they would

never have voted for if

their freedom of choice

had not been so

restricted by the

agreements of the top

politicians of the

alliance? So now a

politician whose party

was elected by just 11

per cent of the

electorate, and thanks

to the direct mandates

won by his alliance

pledges came a distant

third, allows himself to

be made prime minister

at the head of a

completely different

coalition. If anything

is fraud, it is surely

this, and it is fraud

against the electorate!

Now Nepal gets a new

prime minister who long

ago testified that he

was responsible for

5,000 deaths during the

Maoist insurgency. For

long, he has not held

any top office. Nepal's

top politicians,

regardless of party,

usually only accept the

office of prime minister

for themselves.

Otherwise, they prefer

to pull strings in the

background. So now

someone who has pleaded

guilty to a capital

crime has taken over the

highest executive

office.

This is only possible

because KP Oli, with his

78 MPs, supports Dahal

as prime minister. In

view of Oli's past, the

legitimate question

remains how long this

will be. At the same

time, Oli is also an

extremely questionable

figure after all that he

afforded himself in

2021. Both parliamentary

dissolutions at the time

were unconstitutional,

as the Supreme Court has

confirmed, but Oli still

does not accept this. At

least the second

parliamentary

dissolution was nothing

but a coup, which was

only made possible

thanks to the active

support of the state

president.

It is also questionable

to look at the other

parties that want to

participate in the new

government. There is,

for example, the RPP,

which fundamentally

rejects secularism and

federalism and instead

strives for a return to

the Hindu state and

monarchy, i.e. a clearly

unconstitutional

proposal. And in

general, the question

arises how such a party

and a party that calls

itself

revolutionary-Maoist can

sit together in a

government.

Then there are three

parties that were

elected to parliament by

many voters primarily

because they had

contested as alternative

political forces,

notably the Rastriya

Swatantra Party, which

got only 0.4 per cent

less PR votes than

Dahal's CPN (MC), but

also the two regional

parties, Janamat Party

and Nagarik Unmukti

Party. These three

parties are now actually

admitting to ensuring

the stay in power of old

failed politicians. Do

these parties actually

believe that they can

initiate the changes

they promised to their

voters from within the

government? Not one of

the top politicians of

the major parties has

ever explained why he

had to become prime

minister. What they have

all been spreading is

merely empty phrases

that are out of touch

with reality and have

been delivered

monotonously for years.

(27

November 2022)

Attempt of a first

election analysis

The national and

provincial elections

have been held and have

sent shock waves.

Despite massive

manipulation in the

nomination of

candidates, continued

blatant disregard for

social inclusion,

utopian and

fairytale-like election

manifestos and the

subversion of democratic

principles, the

eternally same and long

since repeatedly failed

ageing party leaders

have not succeeded in

deceiving the electorate

once again. The top

politicians were only

concerned with one

thing: they wanted to

have their personal

position of power

confirmed once again by

the elections so that

they could continue

their state-destroying

power struggles for five

years afterwards. All

according to the motto:

Keep it up, it has

always worked so far.

But

it didn't this time. The

voters were, to put it

bluntly, fed up and

taught the top

politicians and their

parties a lesson. The

fact that this did not

turn out even more

clearly is due to

various circumstances.

For one thing, the

insane electoral

alliances led to the

competition between the

parties in the

constituencies, which is

typical of a democratic

system, being

considerably restricted.

Voters could no longer

decide freely. They had

to be satisfied with the

candidates that the

party leaders had chosen

for them, basta! Or else

they had to resort to a

protest vote.

In some constituencies,

a not inconsiderable

number of independent

candidates have favoured

the re-election of

prominent top

politicians. The

nationwide cadre system

of the major parties

also had a supportive

effect on incumbent

politicians. Another

plus for them is the

so-called Constituency

Development Fund,

through which only

directly elected MPs can

specifically promote

development projects in

their constituencies and

thus already work

towards re-election

during the ongoing

legislative period.

Finally, it is also

worth mentioning the

effort to weaken or

exclude potential

competitors through

accusations or even

lawsuits already in the

run-up to the elections.

Sometimes, the Election

Commission seems to have

supported such processes

while turning a blind

eye to the misconduct of

many established

politicians.

Unfortunately, even a

week after the

elections, not even the

FPTP votes have been

fully counted. Regarding

the PR system, only

constantly updated

figures are published on

the Election

Commission's website,

although it is precisely

here that percentage

figures could already

reveal a trend. If you

want to get this one,

you have to calculate

the expected PR seats

yourself.

It is therefore too

early to draw up a

comprehensive analysis,

but some things can

already be clearly seen.

First, there is the

winner of the 2017

elections, the CPN

(UML), whose chairperson

had announced in his

grandiloquent manner

that his party would

emerge from the

elections with an

absolute majority of

seats. In 2017, the

party had won 121 of the

275 seats in an

electoral alliance with

the CPN (MC). This time,

it will be about 40 MPs

less, mainly due to

losses in the FPTP

system. But even in the

proportional system, the

party is expected to

drop by about six

percent to just over 27

percent. In this system,

however, the CPN (UML)

remains ahead with about

the same lead over the

Nepali Congress (NC) as

five years ago.

So, under the PR system,

the NC also loses about

six per cent compared to

2017. Hence, it is only

in the PR system that

one can make out the

status of the parties

among the electorate.

The FPTP system this

time was all about

manipulation by the

electoral alliances.

Thus, the declared aim

of the alliance of the

five ruling parties [NC,

CPN (MC), CPN (US), LSP

and Janamorcha Nepal]

was to ensure a

continuation of the

ruling coalition after

the elections by means

of their electoral

alliance. For this

purpose, the re-election

of as many leading

politicians of the

coalition as possible

was to be made possible.

This plan has obviously

failed. Thanks to

candidate manipulation,

at least the NC was able

to gain almost as many

seats in the FPTP system

as the CPN (UML) lost

compared to 2017.

Together with the seats

from the proportional

system, the party is

likely to have around 90

MPs in the new House of

Representatives. For a

governing majority of at

least 138 MPs, the other

four governing parties

would thus have to bring

in around 50 more MPs,

but it does not look

like that will happen.

Pushpa Kamal Dahal's CPN

(MC), still an alliance

partner of the CPN (UML)

in 2017, is the second

big loser of these

elections. The number of

its FPTP seats will be

halved compared to 2017,

with an expected 18.

Just as a reminder: as

early as 2008, voters

had placed great hope in

this party and gave it

exactly 50 per cent of

the 240 direct mandates

at the time. Since then,

the party has been

declining from election

to election, which is

certainly also due to

the fact that it has

forgotten almost all of

its former ideals. In

the PR system, too, it

will drop by another two

percent, with only about

eleven percent. In

total, this will

probably mean 33 seats

in total.

Madhav Kumar Nepal's CPN

(US), which emerged from

the CPN (UML), is

contesting elections for

the first time. The

election results make it

clear that this party

has not yet reached the

electorate. Although it

is the third strongest

party in the ruling

coalition with 10 direct

mandates, it fails to

clear the three-percent

hurdle in the PR system.

The Loktantrik Samajbadi

Party (LSP), which

recently replaced the

Janata Samajbadi Party

(JSP) in the ruling

coalition, has only four

direct seats, while

Rastriya Janamorcha has

only one direct seat, as

in 2017. These two

parties did not win PR

seats either. From this

point of view, a

continuation of the

current governing

coalition seems at least

difficult, if not

impossible.

Four parties can be

described as election

winners due to their

significant gains. First

and foremost is the

Rastriya Swatantra Party

(RSP), founded by Rabi

Lamichhane in June 2022.

It has won eight direct

mandates and, thanks to

a good eleven per cent

of the PR votes, is

expected to win another

15 seats through the PR

system. As the party's

name suggests, it wants

to establish itself

independently of the

political quagmire of

the major parties, and

this seems to have

resonated with the

electorate, despite all

the defamation campaigns

against this young

party. KP Oli

nevertheless describes

the emergence of this

party as a trivial

matter. The question

arises whether this

expresses arrogance or

sheer shock.

The winner from among

the established parties

is the RPP, which many

had already seen as a

outdated model in 2017

in view of only one

direct mandate and its

failure to clear the

three-percent hurdle in

the PR system. In 2022,

the party won seven

direct mandates and,

thanks to six per cent

of the PR votes, has a

total of 15 MPs. The

party stands for a

return to Hindu state

and monarchy, a clearly

unconstitutional

aspiration. The improved

popularity in the PR

system is probably

largely due to a protest

against the

manipulations of the

major parties. However,

the mere six percent or

so of the PR vote also

makes it clear that the

RPP's aspirations do not

enjoy broad popular

support, contrary to

what is claimed at

rallies of this party.

The two smaller winners

of these elections are

based in the Tarai. One

is CK Raut's Janamat

Party (Referendum

Party). Raut has long

advocated an independent

Madheshi state in the

Nepali Tarai, which of

course also contradicts

the constitution.

Although Raut's movement

did not always establish

itself with greater

militancy, the state

often dealt with him

quite harshly. In 2019,

the then Prime Minister

KP Oli concluded an

agreement with Raut,

which, according to Oli,

meant that Raut would

distance himself from

his separatist

aspirations. This was

countered by Raut's

immediate formation of

his Janamat Party,

which, as its name

suggests, wants to

achieve the creation of

a Tarai state not

through militancy but

through a referendum. CK

Raut has now won the

direct mandate in his

constituency with a

large majority. More

than 2.5 per cent of the

PR votes are also

remarkable. The party is

also winning a number of

seats in the provincial

elections, which will

not be discussed further

here.

The second smaller party

from the Tarai that

successfully attracted

attention in the

elections is the Nagarik

Unmukti Party (NUP). In

the PR system, like the

Janamat Party, it

achieved a good 2.5 per

cent of the votes and

also three direct

mandates. It was equally

successful in the

provincial elections.

The party was not

officially registered

until January 2022. Its

initiator is Resham

Chaudhary, who is

currently serving a life

sentence. He is

considered a prime

suspect in the Tikapur

riots, in which eight

policemen and a child

were murdered in 2015.

Chaudhary was elected to

the House of

Representatives in 2017,

although he was

officially in hiding.

His appeal against his

conviction and its

rejection by the Dipayal

High Court has been

pending before the SC

for some time. He had

wanted to run himself in

2022, which was

rejected.

The rise of the two

aforementioned Tarai

parties can be seen in

the direct context of

the decline of the two

successful Tarai parties

of the 2017 elections.

The Rastriya Janata

Party (RJP) and the

Sanghiya Samabadi Forum

(SSF) managed to win

5.45 per cent of the PR

votes each and a total

of 33 assembly seats at

that time. In the

intervening period, the

two parties even merged

to form the Rastriya

Janajata Party Nepal

(RJPN), which meant a

strong presence of the

Tarai people in

parliament. At times,

Baburam Bhattarai, who

had won a direct mandate

through his Naya Shakti

Party, also became

involved in this party.

The infighting among the

top leaders of the major

parties in recent years

also left its mark on

the Tarai politicians.

First, the RJPN broke

into the Janata

Samajbadi Party (JSP)

and the Loktantrik

Samajbadi Party (LSP).

Initially, the JSP

became a member of the

ruling coalition. When

this party felt

disadvantaged in the

electoral alliance, it

switched to an alliance

with KP Oli's CPN (UML).

Within the government

coalition, the LSP then

took its place. In the

end, it became apparent

that the top politicians

of the Tarai parties

were also primarily

concerned with their own

power and chances of

personal re-election and

not with the concerns of

the people they claimed

to represent. They have

now been taught a lesson

by the electorate in the

parliamentary elections.

The share of the PR vote

fell by more than 1.5

per cent for the JSP and

by a good 3.5 per cent

for the LSP. The JSP

lost six seats, the LSP

13, the latter even

failing to clear the

three-percent hurdle. In

the Tarai, too, people

seem to be voting more

consciously.

It remains to mention

that the Nepal Majdur

Kisan Party was able to

defend its direct

mandate in Bhaktapur.

Five independent

candidates were also

elected. This, too, may

be seen as a sign of

voter dissatisfaction

with the major parties

and their misguided and,

in some respects,

anti-democratic

policies.

What do the elections

mean for political

stability? What might a

future government look

like? The new House of

Representatives will

include twelve parties

and five independents.

In 2017, only five

parties had more than

one MP; this time there

are nine. The then

governing coalition of

CPN (UML) and CPN (MC)

did not bring any

political stability to

the country, despite a

near two-thirds majority

in parliament, but

rather exacerbated the

chaos and infighting.

Rational coalition

governments with a clear

majority of MPs are not

in sight at all this

time.

Only a coalition of NC

and CPN (UML) could have

a majority of about 60

percent of the MPs. But

such a coalition makes

no sense whatsoever if

it is led by the failed

prime ministers of the

previous legislature,

who might then also want

to take turns in office.

If the voters have

expressed anything

definitively, it is that

they want a new

beginning with fresh

faces in positions of

responsibility. The RSP

was also so successful

because it relied on a

much younger generation

of politicians. At best,

it can be criticised for

not having considered

the aspect of social

inclusion much better

than the established

parties (for example,

only 12 women among 131

direct candidates). But

this party is still very

young and this should

not be overrated here.

Calls for a generational

change have also been on

the agenda of the

numerical winner of

these elections, the NC,

for some time.

Immediately after his

re-election, Gagan

Thapa, a younger

politician, laid claim

to the office of the

future prime minister.

Within the party,

several politicians from

the old guard will

challenge his claim.

Apart from the incumbent

Prime Minister and party

president Sher Bahadur

Deuba, these are at

least Ram Chandra

Poudel, Shekhar Koirala,

Shashank Koirala and

Prakash Man Singh. With

a turn towards the

younger generation,

there may finally be

options for a more

hopeful political future

of the country.

(21

October 2022)

The declared ideals of

2006 and today's

political impasse

The

scorn of Nepali

politicians knows no

bounds. The top leaders

of the ruling coalition,

for example, repeat in

monotone that their

electoral alliance is

necessary to preserve

the constitution,

stability and

prosperity. Yet, the

ruling coalition has

failed miserably on all

these three aspects in a

similar manner as the

Oli government before

it.

In

reality, the leaders of

all the major parties

are only concerned with

securing their

re-election. If only one

candidate from the camp

of an electoral alliance

stands in a

constituency, his

chances of re-election

increase enormously.

Only independent

candidates can

counteract this

speculation, if voters

realise in sufficient

numbers that the same

failed top candidates

cannot be re-elected

under any circumstances

in the interest of the

country, the people,

democracy and the

constitution. Another

complicating factor is

that this alliance

system extremely reduces

the number of potential

alternative candidates

of a party. Only the

same old and long-since

failed people are up for

election.

None

of the so-called top

politicians respects the

constitution and laws.

Indeed, they obviously

do not even know them.

Should they

intentionally violate

them, they would have to

be brought to justice

immediately. Their

behaviour would be

highly malicious and

therefore not covered by

any passage in the

constitution and

subordinate laws.

The

failed "top politicians"

are a collection of

male, predominantly

high-caste politicians

who want nothing to have

to do with their own

slogans of 2006, namely

advocacy of social

inclusion, democracy,

federalism and

secularism. For all of

them, only their own

very personal interests

in power and all the

privileges that go with

it count.

16

years have passed since

2006. There can be no

talk of social inclusion

at all. It may have been

in evidence at the time

of the first Constituent

Assembly election in

2008, but it was

systematically

dismantled thereafter.

Even the inclusion

provisions of the

interim constitution

were fundamentally

disregarded. With the

adoption of the new

constitution in 2015,

this was taken further

in a decisive way. For

example, the provision

of the interim

constitution to respect

inclusion in the

selection of direct

candidates, which was

never respected anyway,

was removed altogether.

Their proportion, mostly

hand-selected males from

predominantly so-called

high Hindu castes, was

increased at the same

time. Only 110 of the

275 MPs are now elected

by the people through

the proportional

representation system

(PR). The latter is

increasingly misused by

top politicians in a

nepotistic manner to

infiltrate relatives,

associates and friends

into parliament. Since

hardly any women are

nominated as FPTP

candidates, the

prescribed 33 percent

share of women in

parliament must be

ensured via the PR

system. For example,

putting the prime

minister's wife on the

PR list guarantees her

safe election to

parliament. In view of

the fact that most of

the FPTP candidates are

men from the Tagadhari

castes or Khas Arya

(societal share of these

men = 15 per cent), it

seems downright

grotesque that another

30 per cent Khas Arya

are elected to

parliament via the PR

system. In this way, an

adequate inclusion of

"all" social groups, as

pompously promised by

the top politicians in

2006, will never be

achieved. They don't

even want this, and in

2006 they only talked

about it like so many

other things that they

still pompously promise

today but never really

mean.

Democracy

means the rule of the

people. The alliance

politicians declare in

all seriousness that

they are standing up for

this when they form an

alliance. In reality,

however, this is a

paternalism of the

voters. They are

obviously to be declared

too stupid to recognise

which politicians are

best suited to represent

their interests and the

needs of the state.

Therefore, the alliance

politicians take this

agony of choice away

from them. Voters are

only supposed to cast

their votes for the

common candidate that

the top politicians have

previously negotiated in

weeks of discussion,

regardless of which

party that candidate

belongs to. That is not

democracy, that is

oligarchy and the

dumbing down of voters.

The

idea of federalism was

brought up in the 1990s

by stakeholders of the

Janajati groups and the

then insurgent CPN

(Maoist). Considering

the fact that Nepal had

hitherto been an

extremely centralised

state and that numerous

regions and social

groups were not really

participated, this

proposal seemed rational

and later found its way

into the basis for

discussion in the

Constituent Assembly.

When the top politicians

realised that the

proposals put forward on

the federal state

threatened their

privileges and state

control, they

increasingly took over

the constitutional

discussion themselves.

Their disagreement on

the issue of federalism

ultimately led to the

failure of the first

Constituent Assembly. It

was only with the change

of majority in the

second Constituent

Assembly that the NC and

CPN (UML) were able to

push through their ideas

of the federal state,

which were more oriented

towards the system of

the Development Regions

of the Panchayat period

and denied any

historical and ethnic

reference even in the

naming. Then, when the

constitution was

adopted, the inclusively

elected representatives

in the assembly were not

allowed to introduce the

concerns and ideas of

the social groups they

represented anyway.

Article

3 of the 2015

Constitution defines

Nepal as a multi-ethnic,

multi-religious,

multi-lingual and

multi-cultural state.

Such a state cannot

possibly be linked to

the religion, language

and culture of a single

one of these social

groups. In this respect,

it was obvious to

declare Nepal a secular

state. A look at the

history of modern Nepal

from the days of

Prithvinaran Shah to the

last days of the

monarchy makes it clear

that the close linkage

with Hindu political

ideas and ideals has

been one of the main

causes of social

inequalities,

discrimination and

participatory exclusion.

Despite the now official

commitment to secularism

in the constitution

(Article 4), there are

repeated calls for a

revival of the Hindu

state. These come not

only from those circles

that are

party-ideologically

committed to this albeit

unconstitutional idea,

such as the RPP groups,

but there are also a

number of politicians

within the major parties

who occasionally flirt

with this idea and

closely link their

notion of Nepali

nationalism to Hindu

ideals. The best example

of the latter has been

provided by former Prime

Minister Oli on

different occasions.

This may also be related

to the fact that most

top politicians belong

to a cultural

environment that is

closely linked to Hindu

values and ways of

thinking and lack

necessary understanding

of the multi-ethnic

society. If adequate

social inclusion had

taken place since 2006,

democracy, federalism

and secularism would

certainly not be

questioned today.

(24

October 2021)

Worsening of the national

crisis

The

crisis of the Nepali state

is progressing. After the

coup-like dissolution of

parliament twice and his

removal by the Supreme

Court, KP Oli with his

CPN-UML continues to

"successfully" prevent

parliament from working. His

successor as prime minister,

Sher Bahadur Deuba (Nepali

Congress, NC), is still not

getting anything done after

more than 100 days in

office. A partly

anti-democratic approach and

cracks are also emerging in

this government, the latter

not least because of the

possible signing of the MCC

agreement with the USA,

strongly advocated by Deuba.

With

his appointment of a

brother-in-law of the Chief

Justice (CJ) as minister,

Deuba has also brought the

Supreme Court under

criticism. Assurances by the

CJ that he strongly advised

Deuba not to do so look

implausible. The Bar

Association is on the

barricades, as are the CJ's

colleagues in the Supreme

Court. The judiciary has

been permanently damaged.

The

NC party convention, which

legally should have taken

place by March 2021 at the

latest, keeps being

postponed. The upcoming

party convention of the

CPN-UML also seems to be

experiencing problems. All

four major parties are

showing that they are not

willing to learn. According

to schedule, new elections

are due in autumn 2022 at

all three levels of the

federal system. Moving them

up significantly has long

been called for by the

CPN-UML and is now also

being discussed by the

ruling parties.

But

no matter when they are

actually held, nothing is

likely to change in the

messy situation. The old and

long-since failed leaders of

all parties do not want to

give up a millimetre of

their power and control. In

the NC, only veteran

politicians, some of them

75-76 years old, are

fighting for the leadership

of the party for the next

five years and, of course,

for their candidacy for

prime minister next year.

Oli claims to have set in

motion a huge rejuvenation

process in the CPN-UML, but

has enforced that the

maximum age for election as

party president and for

candidacy for prime minister

is 70. He himself will be 70

in February, so he is on the

safe side. Meanwhile, the

question of whether Oli has

any legitimacy for state and

party office after his

attacks on parliamentary

democracy, the constitution

and the rule of law remains

undiscussed.

Pushpa

Kamal Dahal's CPN-MC has

forgotten all its once

revolutionary claims. It has

become a mainstream party

whose leaders have long been

concerned primarily with

their own profit and power

influence. The ideals they

stood for in the ten-year

militant uprising no longer

count. Not only the Maoist

fighters who put their lives

and health at risk for these

ideals feel betrayed, but

also all those who had hope

for the promised social and

political changes and who in

2008 voted the Maoist party

as by far the strongest

political force in the first

elections to a Constituent

Assembly. Nothing is left

and nothing will come.

What

remains of the major parties

is the recently formed

CPN-US (Unified Socialist)

led by Madhav Kumar Nepal,

which recently split from

the CPN-UML. This party is

still too young to really

classify it. At best, one

can see that even in this

new party, the traditional

patriarchal orientations

have been preserved in the

nominations to the various

party bodies. At most, it

will be interesting to see

how many votes the two

moderate communist parties,

CPN-UML and CPN-US, will

lose in the next elections.

In 1998, the CPN-UML had

already split over personal

power claims. In the 1999

parliamentary elections, the

two groups together received

the most votes for the first

time, but in the fight for

seats in the then

single-majority system they

took the decisive votes from

each other and helped the NC

to an absolute majority of

seats despite losing votes.

The

question remains: What will

the next elections bring for

the country and for the

people? All indications are

that the voters will once

again have no real choice.

They will probably only be

allowed to decide which of

the numerous failed

high-caste male top

politicians they will vote

for. Hopeful younger

politicians of both sexes

and with a view to balanced

social inclusion will

probably continue to be few

and far between. The old

heads in all parties will

ensure that. It already

seems certain that no party

will win an absolute

majority of seats. And Nepal

has not been able to cope

with such a situation so

far.

(10

October 2021) Will

everything be better with

PM Deuba?

Exactly

90 days ago today, Sher

Bahadur Deuba was sworn in

as Prime Minister for the

fifth time. The background

is well known. KP Oli had

tried to cover up his

incompetence in an

authoritarian manner.

Several breaches of the

constitution, repeated

contempt of court and

subversion of basic

democratic norms ultimately

left the Supreme Court with

no choice but to remove Oli.

Previously, Oli saw no

reason to resign, neither in

a clear vote of no

confidence by the House of

Representatives, nor in the

explicit provisions of the

Constitution, nor in the

crumbling support within his

own party.

In

a democratic state, these

would be ample reasons to

deny KP Oli the right to

hold political office for

all time to come. But Oli

does not care about any of

this. Internally, he has

preferred to divide and

possibly weaken in the long

run his CPN-UML, which had

developed into a formidable

left force over the past

decades - definitely not to

Oli's credit. At the

national level, even after

his ouster, he has continued

his efforts to destroy

parliamentary democracy.

Most notable here is the

continuous blockade of both

houses of parliament,

sometimes enforced with

considerable militancy. With

hollow slogans, Oli and his

closest confidants are

trying to give the

impression that an

overwhelming electoral

victory for the CPN-UML in

the next elections is beyond

all doubt. Actually, a clear

age limit was supposed to

initiate a rejuvenation

process in the party. But in

a recent amendment to the

constitution, Oli ensured

that the age limit with

regard to running for

political office was only

set at 70. In February 2022,

Oli will turn 70; before

that, of course, he wants to

be confirmed as party leader

for another five years at

the party convention in

November and then also be

his party's top candidate in

the upcoming parliamentary

elections in 2022.

For

about a year, Oli as prime

minister had blocked the

legislative work of the

people's elected

representatives because he

could be less and less sure

of majority parliamentary

support for his increasingly

abstruse policies. With the

help of the president, who

was compliant with him in

every respect, laws were no

longer passed by parliament,

but were signed by Oli and

then by the president in the

form of ordinances.

Oli's latest coup was the

second dissolution of the

House of Representatives

despite an explicit

interdict by the Supreme

Court. In doing so, the PM

and President knowingly and

single-mindedly disregarded

the fact that a majority of

the members of the House of

Representatives had

expressed in writing their

support for replacing Prime

Minister Oli with Sher

Bahadur Deuba. Only another

Supreme Court ruling could

put an end to their

unconstitutional action.

So,

Deuba has been Prime

Minister for three months

now. On 18 July, he was

confirmed in office by a

narrow two-thirds majority

of MPs in a vote of

confidence. What has changed

since then? In short,

remarkably little. It was

clear that Deuba's power

would depend on support from

several opposition parties

or party factions.

In

his vote of confidence, he

had even received some votes

from the Oli faction of the

CPN-UML. At that time, the

Supreme Court had explicitly

ruled out negative

consequences for voting in a

way that deviated from the

party line. But after that,

the Political Party Act of

2017, in which top

politicians had given

priority to a party line

constraint over a free vote

of conscience by MPs on

votes, was again in effect.

In the worst case, the party

leadership can revoke the

status of MPs who disobey

the party leadership's

voting instructions. All

that is needed is a simple

notification to the

secretariat of the House of

Representatives. In order

for a party's faction to

split from the parent party

without the MPs losing their

parliamentary status, it had

to get at least 40 per cent

of the MPs behind it.

This

arrangement was critical for

Madhav Kumar Nepal's UML

faction MPs. They could not

support Deuba, nor could

they possibly agree to an

amendment to the Political

Party Act in parliament.

However, without such an

amendment, they could not

separate.

In

this situation, Deuba

resorted to the method

previously practised by Oli

and rightly criticised

harshly. Deuba abruptly

ended the session of the

House of Representatives,

changed the number of MPs

required for a party split

to 20 per cent by ordinance

signed by the president, and

reconvened the parliamentary

chamber. Shortly after, the

faction of MK Nepal split as

CPN-US (Unified Socialist).

As the opportunity was

favourable, the faction

around Mahanta Thakur also

split from the Janata

Samajbadi Party-Nepal

(JSP-N), which also

supported Deuba, under the

name Loktantrik Samajbadi

Party (LSP). Soon after, the

Deuba government withdrew

the ordinance amending the

Political Party Act, so the

law is again in force in the

form it was before the party

splits. Deuba had, after

all, achieved what he

wanted. With the parties

supporting him, he could now

hope for the necessary

majority of MPs in votes.

But this had nothing to do

with democracy and

constitutional procedure.

Even

after this "clarification"

of the majority situation,

however, it was to take

weeks before Deuba could

complete his rudimentary

cabinet - four ministers had

been sworn in together with

him, and later Narayan

Khadka was also added so

that he could represent

Nepal at the United Nations

General Assembly. The

reasons now lay in the

dispute between the

coalition partners over the

respective number of

ministerial posts and the

division of the portfolio.

It

was only 88 days after he

was sworn in that Deuba was

able to complete this

process. His cabinet now

comprises 25 people, 22

ministers and three

ministers of state. His NC

has nine ministers and one

state minister, while the

CPN-MC, as the second

strongest coalition party,

has five ministers. The

CPN-US and the JSP-N each

have four ministers and one

minister of state; after

protests, the NC had given

another ministerial post to

the CPN-US.

The

fact that there are five

women in the cabinet this

time can be seen as a

positive development to a

limited extent. This

corresponds to a share of 20

percent. This is the highest

figure, at least since the

Council of Ministers was

limited to a maximum of 25

persons by the new

constitution. However, Nepal

has set itself a target of

at least 33 per cent women

at all levels of the state,

so this is still a long way

off.

The

high proportion of members

of the Newar caste of the

Shrestha is striking. They

make up about one percent of

the population. As Newars,

they actually belong to the

Janajati groups, but in the

Hindu hierarchical thinking

of the state elite on the

basis of the Muluki Ain of

1854, they are classified as

Tagadhari (bearers of the

sacred string), to which

above all the Bahun, Thakuri

and Chhetri belong.

Including the Shrestha, the

Council of Ministers once

again includes 16 Tagadhari

(64 per cent, share in the

total population around 30

per cent). In this respect,

therefore, little has

changed compared to previous

governments. The Janajati

are only reasonably

represented according to

their share of the

population if the Shrestha

are also assigned to them.

The Madhesi are only

involved through the JSP-N

and are also slightly

under-represented.

Surprisingly, once again

there is a Dalit as a

minister (through the

CPN-MC) Since about 12 per

cent of the population is

Dalit according to the 2011

Census, this continues to be

an extremely blatant

exclusion.

Of

course, it is difficult to

put social participation in

the Council of Ministers in

relation to social shares.

In view of the traditional

imbalance, however, one can

still speak of a

continuation of the previous

personnel policy. At most,

it is still noticeable that

the share of Bahuns in the

Council of Ministers has

declined significantly

compared to the Oli

government, although they

continue to be

overrepresented. Perhaps

this is also related to the

fact that the prime minister

himself is a Chhetri this

time. Given their population

share, to have not more than

two Bahuns in the Council of

Ministers would be

appropriate.

The

completion of the cabinet

was overshadowed by another

affair. Even before the

final nomination and

swearing-in of ministers,

there were strong rumours

that Chief Justice Cholendra

Shamsher JB Rana was trying

to gain influence over the

composition of the

executive. There were

already strong protests from

the media, civil society and

lawyers about this mixing of

the judiciary and the

executive.

Unfortunately,

the ministerial list

reinforced these initial

fears. Gajendra Bahadur

Hamal, a brother-in-law of

the Chief Justice, was

appointed Minister of

Industry, Commerce and

Supplies. He was not even a

member of parliament and

came from the district level

of the Nepali Congress, so

if in doubt, he would have

had to become a member of

parliament within six months

if he wanted to retain his

post. Another shadow fell on

him because he had clearly

advocated a return to the

Hindu state in the past. But

he is not alone in this in

the NC; even general

secretary Shashanka Koirala

has repeatedly expressed

this view. In view of the

escalating turmoil, Hamal

resigned from office on the

second day after his

swearing-in.

There

is fierce criticism over the

composition of the Council

of Ministers both within the

NC and the JSP-N. Deuba, in

any case, has already amply

demonstrated that he has not

changed compared to previous

terms. Clearly, he is well

on his way to his fifth

failure as prime minister.

(5

July 2021) Constitutional

crisis : Can it be

solved?

Corona

infection numbers may

temporarily decline.

However, in view of the

unchanged low tests, the

lack of vaccines and the

global developments, it is

to be feared that a third

wave will soon hit. The

vaccination optimism spread

by Prime Minister Oli seems

misplaced.

Meanwhile,

the political situation is

escalating. The Supreme

Court has already rejected

unconstitutional measures of

the Oli government in

various cases. Perhaps

outstanding is the decision

that the personnel change in

the Council of Ministers was

clearly defined as

unconstitutional, thus

reducing the Council of

Ministers to five members.

Oli could have easily read

this in Article 77 (3) of

the Constitution before

making his decision.

Presumably, however, he does

not see himself as an

interim prime minister at

all.

Yet

Oli should not even be an

interim prime minister after

the elected MPs of the

people in the House of

Representatives withdrew

their confidence in him. Due

to the disunity of his

political opponents, no

alternative prime minister

could initially stand for

election. Therefore,

President Bidya Devi

Bhandari appointed Oli to

continue in office as

interim Prime Minister. As

such, according to Article

76, he would have had to

seek another vote of

confidence in the House of

Representatives within 30

days. Had he lost this one

too, his time as prime

minister would have been

history.

However,

the situation changed within

a few days with the

nomination of a new

candidate for prime minister

through a list signed by 146

of 265 possible MPs.

Realising that he no longer

had a chance to maintain his

power through legal means,

Oli staged a coup with the

active support of President

Bhandari. Oli declared that

he had even more MPs behind

him than Sher Bahadur Deuba,

the candidate of the

opposition forces, of course

without a list of

signatures, because this was

not possible at all in terms

of numbers.

Bidya

Devi Bhandari declared the

situation as unclear,

although she only had to ask

the House of Representatives

for a vote. In order to

avoid any more opposition

from the House, she, in

consultation with KP Oli,

dissolved the parliamentary

chamber again, set new

elections for November 2021

and reappointed Oli, who

already had lost the

confidence of the people's

representatives, as interim

prime minister until these

elections.

In explaining this action,

Oli cited contradictory or

unclear provisions of the

Constitution and the

Political Parties Act. Oli

claimed that in a democracy,

elected representatives are

not allowed to vote

according to their

conscience, but must respect

party discipline. In other

words, according to Oli,

democracy is not a rule of

the people, but a rule of

the parties. This is

complicated by the fact that

all of Nepal's political

parties lack democratic

structures and processes.

They are all controlled by a

very small group of mostly

male Bahuns (recruited from

six percent of the total

population). These small

party elites determine party

policy and the voting

behaviour of their MPs.

Even

more serious is the fact

that the respective party

leaders are given an almost

absolute power. All major

parties are characterised by

factionalism. As a rule, the

party chairman is the top

politician who has the most

members behind him at the

two highest party levels.

The party chairman is then

largely free to decide on

personnel appointments as

well as on the party's

political stances.

Resistance comes at most

from the other factions

within the party if he does

not take them sufficiently

into account in personnel

policy.

In

this sense, KP Oli sees

himself as an almost

absolutist ruler over his

CPN-UML. His "world view"

came into crisis when last

year many MPs of his then

still united party NCP

opposed him and eventually

even wanted to replace him

as chairman and prime

minister with another person

from his party. This

situation was aggravated

when the Supreme Court

annulled the merger of

CPN-UML and CPN-MC. This

meant that the CPN-UML was

still the strongest party in

parliament, but had lost its

absolute majority. This

majority was further reduced

when the intra-party

factions of MK Nepal and JN

Khanal continued to oppose

Oli and flirted with

supporting a joint

opposition prime ministerial

candidate. Some of them then

also signed the list

submitted to the president.

Since

then, Oli has been

clamouring that it is

undemocratic for MPs of his

party to disregard his

directives as chairman and

support the opposition

candidate. This aspect will

also play a role when the

Supreme Court has to decide

in the next few days on the

renewed dissolution of

parliament and the

machinations of Oli and

Bhandari.

It

is to be hoped that the

Supreme Court will decide in

favour of preserving

democracy, the constitution

and the rule of law. It will

not be able to avoid better

defining the understanding

of democracy. It is also not

acceptable for the Supreme

Court to make the opposition

candidate prime minister as

is demanded by some lawyers

on the plaintiff's side.

This is not a task of the

court, but of parliament.

The Prime Minister must be

elected solely by the

elected representatives of

the people by secret ballot

and without party coercion.

This alone is democracy! The

Supreme Court should

therefore order an immediate

restoration of the House of